I have read The Tyrant Baru Cormorant. (Despite the best efforts of the publishing industry.)

What a series! Like, damn.

- How we got here

- A brief note on structure

- A slightly longer note on epigraphs

- Defamiliarisation and distillation

- Let’s talk about wizards!

- The resources of the Cancrioth

- Baru’s periapsis

- Let’s talk about tulpas!

- What is a wound?

- Genocide

- The number of interest

- Kimbune’s Theorem

- Barhu’s big plan

- An economic cancer

- History lessons!

- The reason for empire

- The motor driving ‘will’

- Where’s all this going?

- Racialised gender: the downfall of Cairdine Farrier

Last year, I read the first two books in Masquerade series, seeing Baru Cormorant as first a Traitor and then a Monster. Since then, and a great deal of really appreciated feedback, those books have sat in my head accruing emotions.

A quick aside on pronouns and such

I actually had a chance to speak with the author briefly, albeit while they were going through some pretty tough circumstances. (I don't have that line anymore, so if you're reading this, Seth, hi! I really hope I do your books justice and I'd love to find some way to connect again.) I'm going to put a hard line up about speculating about Seth's personal life in this post. Since I don't have a way to check in anymore, I am going to be refer to Seth as Seth since that's the name on the book cover, and use 'they' pronouns because their Twitter bio said 'any pronouns' when it was up. But Seth, if you read this and you are uncomfortable with any part of that please let me know and I'll edit any of these posts.Like the last two posts in this series, this is part review, part meta, part speculation—just an attempt to write down all the things bubbling in my head after I finish a book as rich as this one. Not an attempt to reach a final judgement, but to process the many questions raised, point out some of the things I appreciated, and so on. Just… to give the book the kind of engagement I feel like it deserves.

How we got here

Because it’s been a year since the last, I wanted to recap what this series has been about so far! A lot of this is only revealed gradually, but this is the picture as we have it at the end of Monster. Reading this is not necessary for the rest of the article, but it might be handy to refer back to.

A 2500 hundred word 'summary'

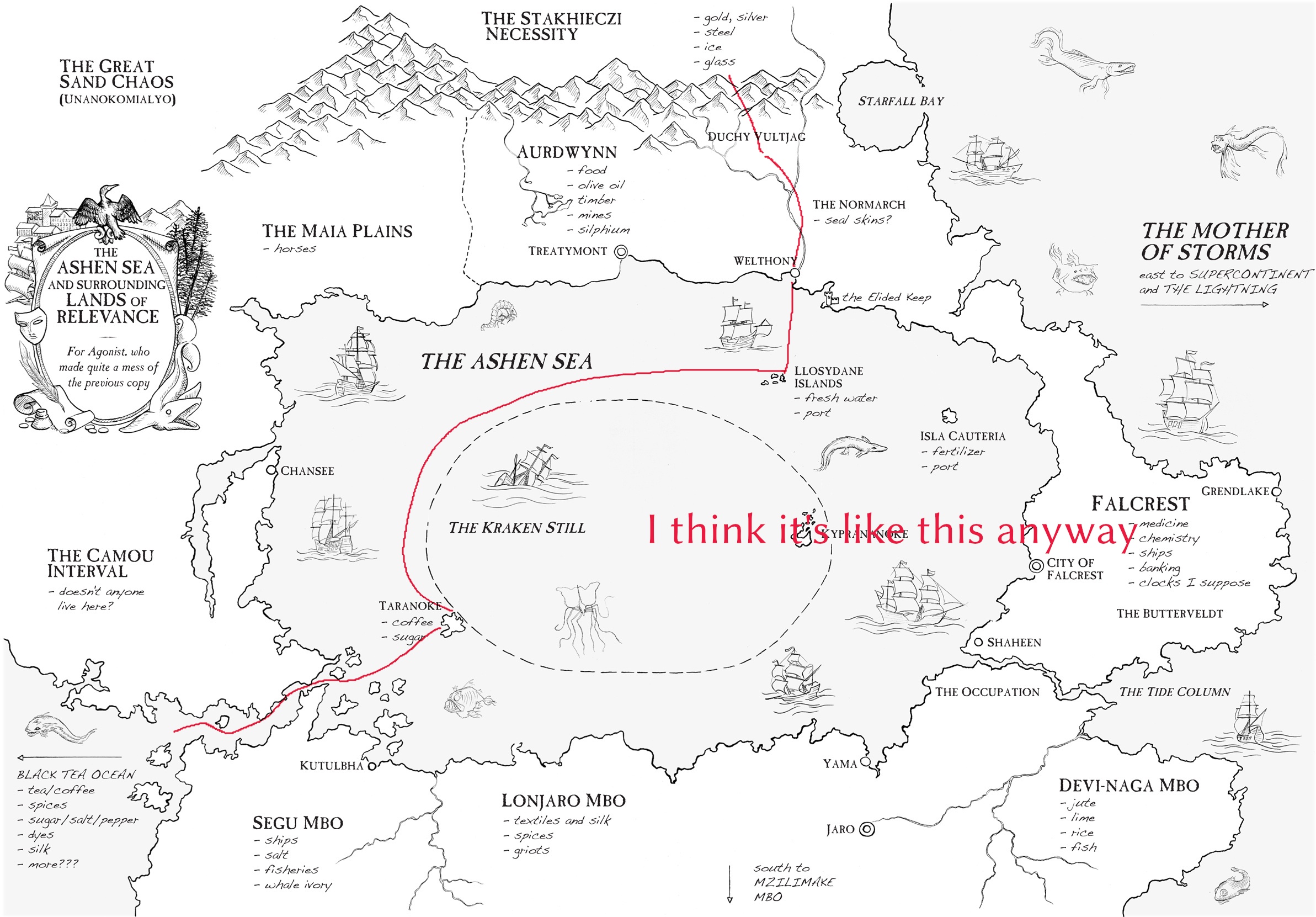

The Baru Cormorant series tells the story of a girl from the volcanic island nation of Taranoke, in a world that is physically similar to our own but with different geography, cultures, and history. But it’s also secondarily the story of a nonbinary Prince Tau-Indi Bosoka from a federation of broadly West African cultures called the Oriati Mbo, and of another secret rebel doing terrible things, Xate Yawa, from a cold feudal land called Aurdwynn, and of an Oriati expatriate navy girl, Aminata.

Chronologically, as I’m presenting it here, the story that we see begins in the Mbo. A small nation called Falcrest has overthrown its monarchy, and its new republican government (nicknamed the ‘Masquerade’) has rapidly started to expand and attempt to take control of the ‘trade circle’ of a sea that somewhat resembles the Indian ocean. In so doing, they challenge the long-standing power of the Mbo, whose diverse people boast of a thousand year history guided by a semi-religious philosophy called ‘trim’, a combination of deontological ethics and conviction in the long-ranging mystical influence of personal connections.

Unexpectedly, Falcrest defeats the Mbo on the sea. After the first battle, two men named Cairdine Farrier and Cosgrad Torrinde arrive in Lonjaro Mbo as part of a hostage exchange. They’re not just any hostages—they’re here of course as spies, each trying to understand how to crack open the Mbo, though they spend a great deal of their time getting tropical diseases instead. There, the Falcresti encounter a trio of young friends: the Princes (gender neutral title) Tau-Indi Bosoka and Kindalana, raised to fulfil an administrative and religious function, and their close friend Abdumasi Abd. As the war drags on, the kids fall out due to teenage drama. Prince Tau, who believes in Trim more than anyone, comes to believe that this falling out is the reason for the war—the large echoing the small.

In Monster, we don’t find out how this part of the story ends. Let’s move the camera to a cold, rebellious feudal nation called Aurdwynn. Xate Yawa is a stable girl living miserably under the aristocracy with her brother. She and her antiroyalist comrades, among them her brother Xate Olake, betray the aristocrats to Falcrest, believing they will do away with the aristocracy. But to her horror, Falcrest keeps the aristocrats around and at the same time, imposes all kinds of eugenic brutalities on Aurdwynn’s people. Yawa betrays an early attempt at rebellion, convinced it is not the time, allowing herself to wriggle into the Falcresti administration. She earns the dubious honour of becoming the person who carries out all the torture, conditioning and lobotomies of the Falcrest administration. But secretly, her goal is much like our main girl Baru: to ‘save’ her homeland of Aurdwynn from aristocrats and imperialists alike, by rising up in the ranks of the Masquerade until she has the chance to drive Falcrest out of Aurdwynn for real. We’ll come back to her later.

Also significant are the Tain family, from the proud but very poor north of Aurdwynn. We have Tain Ko, who has a relationship with Xate Olake (Yawa’s brother) and sides with the antiroyalists, and joins the rebellion against Falcrest; we have her daughter Tain Shir who is one of Farrier’s protégés; and we have her niece, Tain Hu, who ends up the duchess after Tain Shir kills her own mother on Farrier’s orders. At some point prior to that, but offscreen, we know Tain Shir fought a brutal guerilla war in the Oriati jungle for Farrier’s sake; at some point after, she goes off the rails and rebels against Farrier, pursuing her own one-woman anarchist campaign in far more direct ways.

The first book opens on Taranoke. Taranoke’s people have got things broadly figured out: they live off the sea trade with a society organised into extended nonmonogamous families, with relatively little regard for gender. Though there are conflicts between different cultural groups, even war, there is nothing like the brutality that Falcrest will soon unleash. Our picture of Taranoke comes across as near idyllic - not a paper utopia but a place where people are caring, and funny, and living pretty well. Though of course, this is perhaps in part because our viewpoint character Baru fetishises it in distant hindsight, even as she forgets more of her life there.

At the outset of the series, Baru is a child when Falcrest arrives to turn her home into a colony. Falcrest applies all the colonialist tools of exploitation. They play different cultural groups against each other, carefully lending its military power to one side so as to indebt Baru’s people to them; they insinuate their fiat currency into the island’s economy until the Taranoki are increasingly dependent on Falcrest; they use selective innoculations to protect their allies from the smallpox and cholera plagues they ‘coincidentally’ brought with them. And, of course, they build schools to indoctrinate the island’s young people into Falcrest’s ideology of ‘Incrasticism’.

(The specific tenets of Incrasticism we will discuss later in more detail, but we’ll note for not that it is a nasty fascist mix of scientism, eugenics, fetishisation of cleanliness, and Lamarckian delusions about heredity, all effectively oriented towards social control.)

Baru specifically is targeted by a man called Cairdine Farrier, one of Falcrest’s most powerful men and an element of the ‘Throne’ who (at least in their imaginations) are orchestrating Falcrest’s rise to power. She’s subjected to a program of grooming and indoctrination designed to inculcate a deep belief that, for example, expressing her lesbianism or otherwise moving against Falcrest’s interests can only ever end in disaster. In pursuit of this plan, as well as teaching her to associate Falcrest’s methods with power and knowledge and subtly moving to alienate from her family, Farrier has Tain Shir kidnap one of her dads, Salm, and claims to Baru he is dead as a punishment for homosexuality; he has her close friend Aminata attack her over her lesbianism; all the while he’s posing as a merchant, positioning himself as her benefactor and her route to the power to meaningfully oppose Falcrest from within.

Over the course of Monster, we found out that the Throne, far from being united in their methods of would-be absolute rule, are divided between two equally delusional theories of power—but though their theories are delusional, their consequences are very real. So Farrier is in competition with another man, a eugenicist and surgeon named Cosgrad Torrinde. Cosgrad is a proponent of a kind of Lamarckian heredity, believing particles of behaviour are acquired through action and then passed on, so that people can’t escape what he imagines to be the inherent tendencies of their race; he hopes to eugenically engineer the perfect citizen, by discovering a way that behaviours can be surgically implanted. Farrier, meanwhile, believes that his ‘Farrier process’ of operant conditioning can teach anyone to keep their ‘unhygienic’ impulses in check, and his proof is that he’s abused Baru into acting in Falcrest’s interest, not sleeping with other women, etc.

The context of this challenge is that a mysterious woman called Renascent, who has yet to explicitly appear on screen but apparently has hooks in both Farrier and Torrinde, has challenged them to prove their respective theories; the reward will be the blackmail material she holds on the other one. This is not unusual in a way: blackmail is the glue that holds the ‘cryptarchs’ of Falcrest’s secret government together in any semblance of unity. In particular, each cryptarch, upon their appointment, is compromised by an order to execute someone they love. For example, the character Svir—who we’ll meet later—has his partner Lindon under threat of execution for homosexuality. When they cannot go through with it, an exceptional, temporary stay of execution is granted by grace of the (lobotomised figurehead) Emperor—one which will be removed as soon as the cryptarch starts acting up against their patron.

The first book, Traitor, tells the story of how Baru earns the right to be named a cryptarch, in the role of Imperial Accountant for Aurdwynn. Baru’s task is to break the rebellion, permanently; she does this by first financially crushing one attempt, then—on a subtle insinuation from Farrier, via Svir—building up a second rebellion in its place, one credible enough to draw in the troublesome aristocrats who Falcrest wishes to remove and overthrow Falcrest’s incompetent governor, and then at the last minute reveal that she was an agent of Throne all along, bringing all the rebels into one place where Falcrest can liquidate them. Through this convoluted ploy, which involves betraying a very large number of people on the way, Baru proves both her loyalty to Falcrest and her capacity to pull the economic strings to manipulate nations.

In the course of the rebellion, Baru betrays people left right and centre. For example, she pretends to offer marriage to the Necessary King of the neighbouring Stakhieczi for long enough to get their military support, but humiliates him by turning out to be a traitor, putting his position and life at risk. She uses one Duke Unuxekome to get support from Oriati privateers, and through him, unknowingly uses Abdumasi Abd, only to betray them all to the Falcrest navy. And she makes a close ally of Xate Yawa’s brother, Xate Olake, who is hit especially hard by her final betrayal.

But there is one person she stays loyal to: she falls deeply for the duchess Tain Hu, now the ruler the impoverished northern province of Vultjag. She doesn’t allow herself to be with Tain Hu for long, too caught up in Farrier’s indoctrination to associate sleeping with a woman with misery. But they spend a night together on the last night of the rebellion’s apparent victory, before Baru arranges to send Tain Hu away so that at least she will be safe. Tain Hu, however turns herself in, presenting herself as the hostage to secure Baru as a cryptarch—and she is the one who proposes that Baru must kill her, so that Baru can make good on any of the things she believed she could accomplish for Taranoke. So Baru carries out Tain Hu’s execution, seemingly cold-bloodedly, closing Book 1 on an absolutely gut-punch, tragic note.

Monster concerns Baru steadily descending to rock bottom as she reckons with her grief and the conditioning of Farrier. Together with Svirakir, another cryptarch (who is secretly the brother of the Necessary King of the Stakhieczi), Baru flees the mutineer Admiral Ormsment who wishes to bring her down for her role in the Aurdwynn affair. Travelling with Ormsment is Baru’s childhood friend, Aminata, who has become an effective torturer of her fellow Oriati for Falcrest’s navy. She still desperately believes in Baru, and joins Ormsment’s pursuit to find out the truth.

Baru’s head injury, combined with the horrific circumstances of Tain Hu’s death, has left her with a condition known as ‘hemineglect’, where she is unaware of things on the right side of her body, and something close to ‘split brain’ or callosal syndrome. The left side of Baru’s brain is the one controlling her body, and it is not communicating with the right side of her brain. The right side of Baru’s brain has meanwhile come to represent a separate person, which she conceives of as essentially her image of Tain Hu—in Tyrant, the word tulpa is used, but we can get to that.

Over the course of the book, Baru hops between a series of islands, gradually giving in to drink and depression as she wrestles with her fear that she is truly Farrier’s creature, though not without chances to let her awful brilliance shine to crash the odd economy. She and Yawa are each tasked with tracking down the elusive ‘Cancrioth’, essentially cancer wizards and slavers who were long ago overthrown in Oriati legend. Confirmation of the Cancrioth would be immensely valuable for both Farrier and Torrinde, but moreover, the mission is a chance for them to test their respective theories of control: whether Baru, as an exemplar of the ‘Farrier process’, can maintain the control of her behaviour as an ideal citizen of the republic. Xate Yawa, meanwhile, is, by Torrinde’s standard, supposedly far more eugenically suited to this kind of work than Baru.

Torrinde has another project, anyway: the Clarified, who are eugenically bred and conditioned to be pliable servants of the republic, each one answering to a specific command word. This project has limited a success; many Clarified ‘wash out’, and of the two Clarified we meet over the course of the series, both end up breaking from their conditioning (in limited, partial ways—Iscend Comprine, who features in book 2, starts using her own command word). But through their training and specific brand of lifelong indoctrination, the Clarified tend to have pretty fucked senses of ethics, and a lot of lethal skills.

Over the course of Baru’s trip, a great many significant things happen. She becomes something like friends with Iraji, an Oriati boy described as a concubine for Svir, who reacts strangely whenever the Cancrioth are mentioned. She catches up with some of the survivors from Vultjag, and starts sleeping with one, a diver named Ulyu Xe and disciple of the Aurdwynni ilykari religion. And she meets Tain Shir, who has decided to pursue a long project: Shir will chase Baru and punish her for the way she used Tain Hu, and her in-practive devotion to Falcrest, by confronting her with the choice to sacrifice others and mutilating her when she chooses wrong. She also has a bunch of sex with a navy woman, a racist called Shao Lune who’s part of Ormsment’s mutiny. She’s a busy girl!

In the course of her travels, Baru encounters Tau-Indi Bosoka, now an ambassador in their 40s, who at first wants nothing to do with her. But she comes across Tau again as their ship is sinking, and Tau conceives of a ploy to draw Baru into the bonds of trim, by trapping them both in a sinking ship—and Baru ultimately confesses the truth to Tau. So, Tau ends up travelling with her to the island of Kyprananoke.

Kyprananoke is another victim of Falcrest, ruled by the brutal Kyprists who were once Falcrest’s chosen puppet government and, once Falcrest gave up on turning a profit there, held on by sheer brutality and their hold on the water supply. Baru shows up at the Oriati embassy and starts questioning everyone about Iraji, trying to discover if anyone’s connected to the Cancrioth. Admiral Ormsment catches up with the embassy, threatening Baru’s surviving parents in order to force her out to duel. In an attempt at a decisive break from her fall into ethical morass, to break from Farrier’s control, to avoid betraying Tau’s faith in her… Baru accepts. But at that moment, the embassy is stormed by anti-Kyprist rebels infected with an ebola-like disease called the Kettling. To contain it, Aminata, who is watching with her marines, burns the embassy and almost everyone inside.

Baru escapes, and in the chaos, ends up being taken to the Cancrioth ship she was taken for so long. At the outset of Tyrant, she is on the enormous Cancrioth ship Eternal, about to get to grips with the mysterious cancer wizards.

…phew, that’s a lot. And that’s just stuff that’s directly relevant to this book.

In short: in Traitor, Baru betrays the people of Aurdwynn, by playing at traitor to the Masquerade well enough to flush out the genuine rebels. But in truth she is genuinely aspiring to betray the Masquerade, and ultimately she believes herself loyal to Taranoke.

In Monster, she has painted herself as something abominable to even the vicious, blackmail-dominated world of the cryptarchs, someone who would betray her own lover. Or is she a monster because she has been turned into a loyal tool of Farrier, too fucked by his abuse to ever do anything that would make her happy or fail to act in his interests? In any case, from all sides, including herself, she is despised.

Now, we reach Tyrant. By tradition, the name of this book should mean that Baru’s tyrant-ness is ambiguous, arguable in many ways depending who you ask. Let’s see…

A brief note on structure

Traitor was divided into three sections: Accountant, Autarch, Warlord. Monster was broken into the fall of various places: of the Elided Keep, of the Llosydanes, of Kyprananoke. Tyrant is broken up into four sections; three are named after choices—Baru’s, Svir’s, and Yawa’s, each of the three main cryptarch characters—and one named after plague.

A slightly longer note on epigraphs

The first book opened with an epigraph:

A promise: This is the truth. You will know because it hurts.

The second book opens with a followup epigraph:

A question: If something hurts, does that make it true?

The third book opens with a different sort of epigraph, an anecdote from the real-world history that inspired the book:

In 1502 the samudri of Calicut, desperate to stop violent Portuguese incursions into the Indian Ocean trade network, sent two letters. One begged his neighbor the raja of Cochin to close all markets to the Europeans. The raja of Cochin, who saw Calicut as his historical enemy, leaked this letter to the Portuguese.

The other letter offered a blanket peace to the Portuguese admiral, Vasco da Gama.

Da Gama sailed to Calicut to demand reparations and the expulsion of all Muslims. When he was not immediately indulged, he seized hostages, hung them from his masts, and bombarded the city. That evening he sent the severed hands, feet, and heads of the hostages ashore in a boat, along with a note, fixed to the prow by an arrow. “I have come to this port to buy and sell and pay for your produce; here is the produce of this country.”

The note also demanded compensation for the powder and shot used to destroy Calicut.

If the people of Calicut did this, da Gama said, they would become his friends.

I was curious about the history behind this...

Calicut is officially called Kozhikode, and it’s a city on the southwest coast of India, at the time the capital of the state of Kerala. The ‘samudri’ named here are better known by the terms Samoothiri or Zamorin, and they were the long-term ruling dynasty of the city. Many of their individual names have not been recorded, so it is not known which specific Samoothiri leader confronted de Gama and his Fourth Armada, though it is apparently estimated to be the 85th. Kozhikode was at the time a rich city, benefiting from the ludicrously profitable spice trade around the Indian Ocean. The Portugese wanted a slice of the pie: a full cargo of spices would easily fund an expedition and then some. And longer term, they wanted to take over the trade entirely.

And de Gama’s beef with Muslims? That related to the Second Portugese Armada. Portugese traders visiting Kozhikode attacked an Arab ship, believing the Arabs were colluding to shut them out of the spice market. Furious, the Arab traders rioted and killed most of the Portugese; the Portugese blamed the Samoothiri for not doing anything, and started burning Arab ships and bombarding the city. de Gama’s Fourth Armada was explicitly set out to teach the Samoothiri a lesson.

As an aside in this aside, in order to reach India, Portugese ships had to sail all the way around the coast of Africa. The Second Armada somehow accidentally ended up visiting the region we now call Brazil, setting the stage for future Portugese colonialism in South America. But let’s return to de Gama.

You can read more about de Gama’s attack on Kozhikode here. Prior to his attacks on the Samoothiri, de Gama had been sailing down the coast of India (not at that point a unified country). His ‘factors’ (essentially trade-related ambassadors) negotiated fixed-price treaties, and established a system of cartaz licenses which merchants had to have to show that they were paying Portugese taxes.

He also, in an act of particularly astonishing brutality even by the standards of the time (as many chroniclers noted), attacked a Muslim pilgrim ship, looting its cargo and then sealing the passengers in the hold while he burned and sank the ship, and sending his sailors to spear any survivors. The number of people on board is estimated at 200-300.

Then, we get to the anecdote above. It’s pretty much as described. Part of what was at contention was compensation for the riot in 1500. de Gama demanded nothing short of full compensation for the loss of the Portugese factory (not as in a manufacturing plant, but as in a place where factors work), and refused to acknowledge the Samoothiri’s points about how much de Gama had already taken from Kozhikode.

As for what happened next, the 85th Samoothiri refused de Gama’s ultimatums. de Gama continued his bombardment, levelling the poorer districts, but left a blockade rather than land troops to completely sack the city. He hoped that the Samoothiri would eventually come to terms. This attack completely froze trade on the Indian Ocean for a period, and de Gama sailed around for another few months, negotiating another fixed-price treaty in Cochin.

However, de Gama was not ultimately successful in crushing the Samoothiri, who was able to recruit privateers through de Gama’s blockade to attempt a naval defense of the city. de Gama defeated the Samoothiri’s fleet decisively, but the incident left him afraid the Samoothiri would continue to resist, perhaps even allying with other European powers. He returned to Portugal to declare it would take more force to crush the Samoothiri and maintain Portugal’s holdings in Indiia.

The Samoothiri, meanwhile, sent an army over land to Cochin to demand their Portugese factors, and ultimately burned Cochin down, but was forced to leave the city when the Fifth Armada showed up. Kozhikode would continue to battle the Portugese for the next century; there was briefly a Portugese fort but the Samoothiri burned it down. But the city would not escape colonialism altogether: more than two hundred years later, Kozhikode would be conquered by Hyder Ali from Mysore, an ally of the British East India Company. After some time in exile, the Samoothiri would eventually return to Kozhikode as pensioners dependent on the East India Company for their income, but this ended after India became independent. They’re still around today, managing certain Hindu temples, and trying to get the Indian government to start paying them again.

What bearing does this have? For a fantasy novel series, Baru Cormorant is unusually rich in culture, history, and especially, thought-through economics. But it’s still not as absurdly complex and messy as our own world’s history. This is something of the nature of ‘world building’…

Defamiliarisation and distillation

What is the purpose of creating a fantasy novel, rather than merely writing about history directly? After all, even the densest, most thought-through fantasy world will always be a slim imitation of the cacophonous mess of ‘everything that ever happened on Earth’!

For me, it’s something akin to a line drawing vs. a photorealistic painting. The painting tries to create something as close to the light field we might perceive at the eye as possible. The drawing strips away a great deal of information; instead, it attempts to draw out something essential. It tells a story about how things fit together, about what the artist notices.

A fantasy novel is similar. There are many takes on ‘world building’, some very negative (‘the great clomping foot of nerdism’) and some positive. In recent years, various articles and youtube videos have sprung up offering advice on how to make your ‘world’ plausible in terms of geology, climate, etc. But all of this can seem very self-indulgent—not at all a bad thing, I like world building for fun!—without an actual purpose behind it.

Baru Cormorant is, of course, a series about colonialism. It wants to understand the mechanism of the history that created this present world order, of capitalist domination by the rich countries, and poke at the question—I believe—of how it may be broken. The question Baru asks at the beginning of the first book—why do they have all the power, and not us?—frames the series, especially since she offers an answer near the end of this book.

In this vein, worldbuilding represents a kind of thought experiment, or hypothesis. The underlying question is: how do people and societies work? The claim is: this is a plausible course of events. And by observing it, and considering it carefully, we might get an angle on the real world, also.

Why should Baru go to such lengths to build an imaginary world with a complex history, extensive cultural and ideological variation, and economics? I think the subject matter demands it. If you are to understand colonialism, you have to understand how its economics work; you need to understand how it produces its own colonialist subjects and keeps them working towards colonial expansion; you need to understand that (contra books like Imperial Radch), colonialists rarely took control through overwhelming military strength, but played off factions against each other, lending poisoned ‘support’ to make useful allies and puppets. If you try to write a simple story about resistance against colonialism, you will fail to understand your subject.

But it’s not just dryly relating things that actually happened; it is a dramatisation, compressing centuries of not much happening into a few decades, placing intense, dramatic personalities at the centre, and enticing us with weird alternative possibilities. Approaching it indirectly.

As such, it takes various measures to defamiliarise us from the history it’s drawing on. ‘Defamiliarisation’ is a technique in science fiction and fantasy where an everyday thing is described in unfamiliar language, to draw attention to it. Baru Cormorant does this a lot.

Not for everything: reading Baru Cormorant, I noticed that obscure technical terms would often be used without replacement. For example, I would occasionally have to look up words for parts of a boat, such as ‘coaming’, which refers to the bits around a watertight doorframe. However, more familiar ones would be given alternative names with similar etymologies.

For example, the Masquerade does not call people ‘homosexual’, but ‘isoamorous’; its homophobia is rooted in its eugenic philosophy. It does not call people ‘lesbians’, but ‘tribadists’; not ‘gay men’ but ‘sodomites’. Obviously, there is no biblical city of Sodom in this world, nor a Greek origin to offer ‘iso-‘ roots as an alternative to ‘homo-‘. But this substitution is defamiliarising—it lets us look at the Masquerade’s vicious homophobia in a slightly different light, calls attention to its specific ideological component to illustrate how something like homophobia functions.

The same trick is performed with certain common mathematical and scientific terms. Rather than \(pi\), they speak of the ‘circle number’, rather than \(e\) (Euler’s number) they speak of the ‘number of interest’ (as in, compound interest, where money rises exponentially). Rather than the North Pole, we hear of the ‘lodepoint’. These alternative names are rarely all that difficult to parse, and more obscure technical terms—particular in economics—are usually used without obfuscation, even with explanation.

To me, the purpose of all these tricks is to make the setting feel familiar enough to be comprehensible, but distant enough to be subject to scrutiny. The role of science is particularly interesting—in some ways, these books are much more science fiction than fantasy. Many of the weirder things in the book, like transmissible cancers, Baru’s mental state, or the Faraday cage people in lightning land we briefly glimpse at the end, have a basis in scientific research.

But though this book is based so heavily on science, it is deeply skeptical of the institution of science. In Baru’s world, as in ours, science is bound up with power, always. In the present, the Falcresti ideology of Incrasticism is a blend of familiar scientific truth and outright delusion, such as ‘Torrindian heredity’, but its proponents are oblivious to which parts are wrong. One chapter is directly titled ‘epistemic violence’, in which Baru witnesses a massacre by the Canaat rebels of Kyprananoke, who have correctly learned that Incrastic ‘hygiene’ is almost always a tool used by their oppressors to control and mutilate them, and in response have developed an ideology where all tools of Falcrest, from surgery to quarantine, are to be violently purged from the political body. (This seems to be an allusion to, for example, the Khmer Rouge treatment of ‘intellectuals’ during the Cambodian genocide, and the resistance to vaccination faced by white-controlled health NGOs.) I have more to say about this, but we’ll come to it later.

Through making science just a little unfamiliar to the presumably scientifically literate reader, we’re pretty obviously (to me) invited to view our own institutions of science with the same wariness that the characters view Incrasticism. Though this might be me just seeing confirmation of my existing beliefs :p

Mind you, it’s not a case of ‘rational European-analogues, mystical foreigners’. Science is not just a weapon held by Falcrest—we are often reminded that scientific techniques originated in the Oriati Mbo, contra the low opinion held of them by Falcresti racism (or ‘racialism’ as its termed in this world). At one point, we’re related the history of the Cancrioth… which means it’s time to talk about wizards.

Let’s talk about wizards!

In the last review, I declared my reservations about the concept of the Cancrioth. Their reputation is built up over the course of that book as shadow rulers equal and opposite the Falcresti cryptarchs, blessed with radiation-themed magic. As we meet the Cancrioth at the end of Monster, it starts to seem like their reputation has some truth: they do seemingly impossible things like cultivating transmissible tumours, even implanting them into a whale; they light their ship with radioactive light.

In this book, the Cancrioth are pretty quickly deflated in some ways, but in others their role becomes more apparent. Far from the secret rulers of the Oriati Mbo, as the cryptarchs project, the Cancrioth are a fairly obscure cult of cancer worshippers who rule almost nothing, but cultivate transmissible tumours in their bodies, trying to keep each ‘line’ alive since it is believed to contain an immortal soul. Beyond this knowledge, their only real asset is a very large ship, the Eternal, with a lot of expensive things on board. But this ship is a relic, and its cannons are useless against Falcresti warships.

Yet in a certain sense, the Cancrioth are wizards—or perhaps it would be better to say magicians. For this reading, I’m going to go slightly left field and refer to an entirely different book, Stations of the Tide by Michael Swanwick. In this book, a bureaucrat goes to a planet held in a technologically limited state to pursue a magician who has stolen some forbidden tech. As he makes his pursuit, he’s drawn into mysticism, and various psychological tricks that work to convince him that his quarry is powerful and dangerous—a reputation he’s carefully built, drawing on this world’s mythology around transformation, traditional alchemy, etc. etc.

The bureaucrat is constantly questioning the nature of ‘magic’, while getting increasingly drawn into its rituals. As he learns about his target, the Gregorian, it becomes increasingly apparent that the magic is mostly various kinds of nasty ritualised abuse, self-serving philosophy, and manipulation. What makes the Gregorian an effective magician is his ability to convince other people he holds power, to get the whole world to play along with his performance.

Now let’s talk about John Dee, the man who coined the term ‘British Empire’ and advocated for its creation. John Dee was an alchemist and a mathematician and astronomer/astrologer etc., who spent much of his later life trying to figure out a way to commune with angels. And he had power, in large part due to his learned reputation. He was one of the advisors to Queen Elizabeth I, including on astrological matters such as the most auspicious day of coronation, and a navigational advisor on many of England’s voyages to conquer and claim various parts of the ‘New World’. He was associated with another alchemist, Edward Kelley.

In this time, to be a successful alchemist was to convince a feudal noble that you could advise them on spiritual and scientific matters—the philosophy of the time recognising no such distinction, though the question of whether one was a good Christian was more pertinent. After Dee’s death, he was surrounded by rumours about his sorcery—whether, for example, his communications with angels were actually evil spirits. A modern scientific view of people like Dee is of course to dismiss him as either deluded or a con artist: of course there were no angels. But Dees rhetorical positioning of himself as an occultist full of secret knowledge gave him influence.

The Cancrioth are practicioners of this sort of magic. There are a handful of major Cancrioth characters, each named for the location of their tumour: the Womb, the Eye, the Brain. They have no chain of command as such, but the crew of Eternal is divided into factions: the Brain wants to push Falcrest and the Oriati into war as the only answer to Falcrest’s imperial aspirations; the Eye and Womb would prefer that Eternal pick up Abdumasi Abd (who, it turns out, is a Cancrioth member) and go home.

At one point, Baru and Iraji engage in a spiritual confrontation with the Brain. Although Iraji was selected as the bearer of a particular tumour, for which he is well-suited as a host (the Cancrioth’s tumours can enter into benign symbiosis with their host, or kill them), he does not have a tumour, thus he has no magic power in the Cancrioth’s eyes. Tau figures out a way to grant Iraji power: Iraji puts a cancerous pig’s brain, full of malignant tumours, in his mouth.

It wasn’t the first magic Aminata had ever seen. The Oriati pirates she’d fought commonly used sorcery, the sympathetic destruction of Falcresti flags and uniforms and the use of spirit circuits to hold back fire. But this was the most violent, the most sudden, the most appalling in its effect.

He screamed at them through the cancer, and when the Termites heard that wail, when they saw the moaning man coming at them with cancer in his teeth, they all began to shout and to pull at each other, a diffusion of fear, so they would all have the excuse of someone’s else tugging arms to explain the retreat. “Incrisiath!” one of them screamed. “Incrisiath! A sorcerer!”

We see this scene through the eyes of Aminata, an expatriate Oriati who holds Falcrest’s skepticism towards Oriati magic, but also fears, based on Falcresti notions of heredity, that somehow her Oriati background will make her subject to magic:

Iraji screamed at her. Speak through it, Tau-indi had told him, speak so your voice becomes its hunger and when she hears that hunger she will feel her own immortata rise to answer it. It is the nightmare of all the onkos to be devoured by their own immortality, and for their Line to end in malignancy. Worst of all for the Brain, for her tumor is in her thoughts.

The Brain’s hands flew to her head. She fell to her knees on the clay-tablet flooring, and Aminata saw, distinctly saw, that there were tears of pain in the Brain’s eyes.

The magic worked.

At that sight she felt a cold twinge of migraine behind her own right temple. “No,” she said, out loud, “no, not me.” But she could feel it, she could feel the scream in her head.

It worked on her, too. The magic worked on her too.

This confrontation works, because to refuse the magical performance would be to deny the terms of the Brain’s own power as an ‘onkos’ (cancer holder).

There was a chance, even then, that the Brain might have refused him, and fought. One of the Termites might simply have shot Iraji. But there were people watching: the Brain’s people, her navigators and sailors, the educated folk who believed hard in her and in the terms of her power.

If a Termite dared interrupt this confrontation, then the Cancrioth would see sacrilege. And if the Brain did not yield, then her people knew, the way all believers know what they believe, that she would be struck down. Her tumor would swell up and drive her mad.

And she knew they knew it, in the way that one brain considers the knowledge of another.

“I yield,” she said. “I grant you passage.”

Like all stage magic, it’s in the presentation. In simple, physical terms, all that happens is that one person puts something gross in his mouth, risking infection by a malignant tumour, and shouts at everyone. But Tau-Indi, though not a sorceror themself, has understood the symbolic logic of the Cancrioth well enough to turn this gesture into a challenge to the Brain’s own power.

Later, Baru has a discussion about the nature of magic with Ulyu Xe:

Barhu grounded them in a flood meadow and showed Xe how to take temperature readings with a mercury thermometer.

“It’s like magic,” Xe said.

“It absolutely is not!”

“You told me that masters in Falcrest spend two years calibrating each thermometer to the tenth of the degree. That they must be stored with a certain ritual. That they can kill you if you break them open. That they must be destroyed before falling into foreign hands. That they can tell when people are sick before they even know.”

“But this thermometer works by clear, well-understood logical rules. Magic doesn’t work at all.”

Xe lay down on the bank and trailed her bare toes in the water. “You’d only be satisfied if magic were like a rag novel. A wizard shoots a bolt of lightning to animate a corpse. A warlock calls down a star from the sky to blind his foe. But that’s not really magic. It’s just made-up science.”

“No it’s not!” Barhu sputtered.

“Yes it is. If you can see how it works, it’s science. If a wizard were to show you a book of rules by which he combines various gestures and words and gems and metals to make his spells, it would be science, not magic.”

“What isn’t science, by your definition?”

Xe rolled onto her back and squirmed out of her skirtwrap. “When a witch raises a rabbit with the same name as a man, and kills and skins the rabbit, and then pisses through the rabbit’s skin into a pit of gravel, and the man gets kidney stones. The witch never touched the man. She never acted upon him. She only touched symbols of him.”

“Oh, fine.” Barhu crossed her arms and glared. “So magic doesn’t work except when it can be disguised as the coincidence of symbolic manipulation and natural occurrence? That’s very powerful.”

“The most powerful thing in the world,” Xe said, untying her strophium and sliding deeper into the water.

I think there is something deeply true at the heart of this. Ultimately, the difference between a wizard calling forth a holy light, and a person turning on a lightbulb, is the social meaning that we give to these acts.

And there is still a great deal of ceremonial magic even surrounding our ‘more accurate’ scientific understanding of the present. How does a crank mathematician, trying to explain how Einstein is wrong, actually, attempt to build an image of credibility? How does Andrew Wakefield build up his reputation as he peddles pure bullshit about vaccines? They replicate the symbols of science: degrees and doctorates, dry passive voice language, so on and so forth.

The Cancrioth too are scientists as much as wizards. When Baru speaks to the brain, she learns more about their actual history, not as magicians but as scientists.

I talked in the last article how one of the deep concerns of Falcrest is civilisational collapse—a collapse mirroring the fall of historical empires, especially such terms as the Late Bronze Age Collapse, or the fall of the Roman Empire, in our world. In Baru’s world, the most recent great empire to fall was known as the Cheetah Palaces, more than a thousand years prior to the events of the book. In their wake, various slave societies sprang up known as the Paramountcies. The Cancrioth developed out of the various parties in the Paramountcies assigned the work of stopping the slaves dying quite so much: advisors, educated slaves, and mystics. The weapon they discovered in their ‘Work Against Death’ is nakedly the placebo-controlled clinical trial:

It was Alu, lamchild of a priest-linguist, who suggested the method of home-group and journey-group that would revolutionize the world. Alu wanted a better way to test the medicinal effect of jungle plants. Alu knew a story about twin princesses, one of whom went out into the world to journey, one of whom stayed at home in the palace to study, each swearing to learn whether worldliness or scholarship made a better queen. The story was about the value of a monarch connected to the people and the seasons: but Alu extracted a different lesson from it.

The traveling sister had to leave a twin at home so she could learn how her journey changed her. How could you know if a medicine was successful without a group of untreated slaves “at home”? Maybe your new drug was no better than rest and bed care. If you were going to bring a plant to your lord as a panacea, if you were going to ask your lord to spend farmland and labor raising that plant, you had better be damn well sure it worked.

And it did work. Alu’s method worked. It condensed the whole Work Against Death, the entire menagerie of apotropaic magic, poisonous brews, and ritual surgeries, into a rigorous grid of tests that filtered the gold from the water.

The success of this form of scientific medicine motivated a similar reaction as it has in our world: the rich and powerful got big ideas about becoming immortal. But while our would-be liches look to tech like reparative gene therapy, the rulers of the Paramountcies ended up pursuing a different route. They discovered a part of the continent Oria where uranium deposits were close to the surface, ‘hot caves’ (presumably natural nuclear reactors like Oklo Mine) and ‘secret fire’. In our world’s language, what they discovered was both radioactive material and an ecosystem of bioluminescent animals and plants which responded to the presence of ionising radiation, like the radioluminescent paint used in old glow-in-the-dark radium clocks.

But the discovery of this water that inculcated cancer took a different route. The Cancrioth, and their masters, became convinced that tumours could carry an immortal soul, passed between bodies. They managed to selectively breed tumours which could exist relatively benignly in a human body, and treated the carriers of these tumours as incarnations of the same, immortal individual. And they started using those radioluminescent pigments, along with samples of uranium, to create a tradition of magic, in the terms described above. Of course, handling radioactive materials so carelessly risks radiation poisoning and cancer—but cancer is the whole subject of their cult, not something they fear! Sometimes, individuals may die to a cancer turned malignant, but as long as the transmissible cancers live on, those lives are not lost.

So, what do I make of the Cancrioth now I know better what’s being done with them? Previously, I thought of them as a sort of intrusion of overtly fantastical elements into a relatively grounded story. I have come around: I think the Cancrioth are compelling characters, as much as the others in the book, and that a cancer/radiation cult is not much more a stretch than what takes place in Falcrest. This book feels, to history, like a carefully-composed chiaroscuro painting vs. a photograph of nothing in particular. It’s not that the painting portrays something overtly unrealistic, but it is all arranged as a novel, an exciting story full of emotional swerves and character drama and secrets, taking artistic liberties where it needs… rather than simply repeating the banal repetitive messiness of much of history.

At the end of the book, Seth comments in an author’s note on both the Cancrioth, and the new society briefly glimpsed at the end:

In the acknowledgments to the last book I cautioned the reader that stranger ways of life than the Cancrioth’s exist in Baru’s world. We have now received a small glimpse into one of those strange ways. As ever, I leave the question of supernatural power versus scientific unknown in your hands. But I admit I am particularly proud of this one: it gives me special delight to invent things which probably could happen on Earth, had things gone a different, stranger way.

I am actually pretty into this! It just took me a bit to readjust. It’s funny—it seems now that each book addresses the reservations I had with the previous.

The resources of the Cancrioth

So, the Falcresti cryptarchs believed the Cancrioth to be their equal and opposite, secret aristocrats who ran the Mbo from behind the scenes. Even certain Mbo characters, like Tau at the depths of their despair, are disgusted by the thought that the Cancrioth were secretly intervening to manage things, rather than simple Oriati goodness:

“When the Maia invaded, and we thought we’d embraced them into peace, why, it was probably the fucking Cancrioth that set the beetles on their heartland crops! When we appealed to our common decency to stop the displacement of the jungle people, it was probably the fucking Cancrioth who bribed the migrants to turn back! And how about Taranoke, hm? Were you a Cancrioth breeding experiment? Maybe it was a game for them. Maybe one of them bet another, oh ho, watch, I’ll turn the fierce Maia into pineapple-eating sluts!”

But there is no evidence Tau is right. From what we actually see of the Cancrioth, their powers are highly limited. Their ship is ancient, overly large, and its diverse crew is not enough to run it properly. They are constantly low on water, and the loyalties of the crew shift between the different Onkos. The ‘shadow ambassador’ Baru was tracking, who we now refer to as the Womb, probably was not actually doing any spy shit after all. They have an alliance with an actual Oriati spymaster, but there’s no sign they’re actually in control. Eternal is sailing around looking—like everyone—for Abdumasi Abd, so they can recover his tumour, but meeting little success.

What of the times when the Cancrioth does wield influence? In Tau’s flashback ‘Story About Ash’ (which turns out to be a story-within-a-story, related to Baru near the end of the book), a sorcerer comes to Prince Hill—not actually a member of the Cancrioth, but using their methods—alongside a mob seeking the deaths of the Falcresti guests, Torrinde and Farrier. This sorceror does the flashy radioluminescent stuff, but they also demonstrate a strange immunity to pain, which is not explained. If we wished to give a scientific explanation, we might suppose she was on drugs, or had surgery.

Another time is of course the Brain passing on samples of the Kettling, though the Womb is emphatic that the Cancrioth did not create the disease. And the final time is the end of the book, when the Brain—who has herself cast in bronze—becomes a messianic figure for the anti-Falcrest war movement.

And their boat? Eternal is described as almost implausibly enormous, labyrinthine, and junk-rigged with eight masts, about 400 feet long (120 metres). A ship of this size has plenty of historical basis, particularly in the treasure ships of Zheng He, of China’s Ming dynasty, which had up to nine masts. The largest of Zheng He’s ships has been estimated at 135 metres by 55 metres; they would not have been particularly manoeuvrable, and nor is Eternal (Baru discerns some technical notes about its metacentre at one point).

For all its size, Eternal cannot compete with Falcrest’s torpedoes, copper hulls, and incendiary weapons. It only survives its one battle by the intervention of a second Falcresti warship in its defense. The Cancrioth are rich, and weird, but not particularly powerful players, except insofar as what they represent. Much of the book is spent trying to prevent Eternal from being sunk.

Baru’s periapsis

I’ve talked a bunch about the nature of the Cancrioth, but most of this is revealed in the first few chapters of the book. What does this all mean for Baru herself?

Of course, as with the previous, the book traces Baru’s development as she tries to stay true to her project of destroying Falcrest, while slowly going ever further to pieces. Where we left her at the end of Monster, she was in an awful state indeed: on the run, with few friends who don’t despise her, narrowly avoiding being lobotomised, in a deeply fucked up relationship with Shao Lune, drinking heavily, missing her fingers, increasingly losing to depression (here known as the ‘Oriati emotional disease’ because Falcrest, racist, you know). She’s been persuaded by everyone around her that her every action secretly advances the cause of Cairdine Farrier, no matter how she tries to escape his shadow.

At the beginning of this book, Baru decides on a desperate plan to make it all worth it, to ‘write Tain Hu’s name in the ruin of them’ as she once silently promised the dead Duchess. Her old plan was to provoke open ‘hot’ war between Falcrest and the Mbo, along with various other parties; a war that would be catastrophic for most of the world, but would absolutely annihilate Falcrest.

After meeting the Cancrioth, she seizes on a more direct idea: if she can bargain with the Brain, she can get a sample of the Kettling (not at all radiation poisoning, that was my misreading, the symptoms and transmission make it clearly ebola), and release it close enough to Falcrest that the plague will wipe out the city. And, of course, with its long incubation time, the pandemic would soon spread to everything else that is connected to Falcrest by the trade lines… but Baru at this point has set herself on destroying Falcrest, whatever the cost.

On Eternal, she wakes up to (rather inept) torture, and has a brief meeting with Tau. Tau, who, distraught over the ritual the Cancrioth performed to sever him from the web of Oriati social relations—a ritual he fervently believes in, pretty much alone among the cast, Oriati and otherwise—tells Baru that the events at the embassy demonstrate that all her fears about herself are true:

“Dare what? Talk about the woman whose death you use to justify your atrocities? She gave you permission to do a terrible thing. Now she is dead, so she cannot withdraw her permission. But you know her permit only reaches so far: it does not extend to Iraji, or to me. So you’re waiting for me to give you permission to sell Iraji and Abdumasi to the Cancrioth. You want me to say, at least we’ll be together again, damned together in chaos, Abdu and Tau. Really, you’ll be doing what’s best for both of us. Is that right? I think it is.”

“Tau…”

A smile sweet like sugar rot. “You need me to be your little amphora, your bottle of reserve goodness, to shatter and use up. You’ve been dying a slow death since you killed Hu. You need to take another soul to finish your work. Only it’ll never be done. You’ll always need more. And no matter what you do here, Baru, I expect that by some strange coincidence it will end up being what Mister Cairdine Farrier wants. Don’t you think so, too?”

Which hits Baru’s anxieties like a shaped charge.

With all that on her mind, she ends up taking an offer of stolen cocaine (here known as ‘mason dust’) from Tain Shir as a way to spur herself into action. On that high, she confronts the Brain, and tries to negotiate for the Kettling. The Brain’s price is simple: Baru must infect herself with a deadly, malign transmissible tumour, guaranteeing that she has no interest in defecting to Falcrest to survive, and committing her to the end of Falcrest’s world.

When Baru can’t go through with it, her entire world loses its last vestige of structure. Her promise to herself was that all her sacrifices were for the ultimate good of Taranoke, and for Tain Hu specifically. Tain Hu sacrificed herself for Baru’s mission, and in Baru’s warped logic, she ought to be willing take the same sacrifice—and if she won’t give herself cancer, well, she must just be Farrier’s creature after all!

(The right side of Baru’s brain does not agree that Tain Hu would want her to die of cancer, funnily enough.)

By the time she is forced out of Eternal by Xate Yawa performing a ploy with Iraji’s life, she’s more or less outright suicidal. Tain Shir shows up with yet another ‘lesson’, and Baru, exhausted of the things she’s done, tells Shir to take her, not Ulyu Xe.

This is the bottom of Baru’s arc, and the beginning of her roundabout path to being something like a functional human being. But the impetus comes from a rather unexpected source—Xate Yawa.

Xate Yawa, we may recall, had a plan to deal with the humiliated Necessary King of the Stakhieczi: she would send him a lobotomised Baru as dowry for a marriage to her puppet governor Heingyl Ri, to demonstrate his revenge and secure his own power over his people. She’s seen Baru as nothing but a thorn in her side this entire time, and—after the rogue Clarified, Iscend Comprine, intervenes to stop Tain Shir executing Baru on the spot—she finally has Baru on her operating table. But at the last minute, curiosity gets the better of her, and she performs some experiments on Baru’s split brain, using the suggestion of a lobotomy to manipulate Baru into telling the truth. (As so often in these books, the suggestion of a thing is more important than the thing itself…)

So Xate Yawa is the first to figure out that Baru has a tulpa of Tain Hu running the right side of her brain.

Let’s talk about tulpas!

If you’re very online, like me, you might well have encountered the notion of tulpas in certain fandom subcultures (related to other fandom-occultism such as transformation hypnosis tapes—for some reason these things were quite popular in the My Little Pony fandom subculture). A tulpa is an independent sapient mind inside one’s own head. Unlike typical ways of being a multiple system (‘DID’), it is something deliberately cultivated. The term is actually one from Tibetan buddhism, but reinterpreted by Western occultists in a way that has relatively little to do with its original context. Practioners claim that, with the appropriate ritual practice, they can cultivate a tulpa in their mind, and communicate with it.

As we discerned in the last book, Baru is suffering from something close to ‘split brain’ or ‘callosal syndrome’. The two hemispheres of her brain have stopped being synchronised, except in particular moments of seizure induced by (for example) drugs. Baru’s left brain considers itself continuous in identity with her original self; Baru’s right brain considers itself to be Tain Hu. In effect, Baru has accidentally created a tulpa of her dead girlfriend. Occasionally, Tulpa!Hu will intervene in the narration through right-aligned text.

The word is used directly, when Yawa figures out what’s going on with Baru, along with an alternative, ilykari word, eryre. The fact that ‘tulpa’ is specifically identified as [a translation of] an Alphalone word suggests it’s not necessarily the notion of ‘tulpa’ we’re familiar with. Yawa offers a slightly more mystical interpretation: Barhu has cultivated Tain Hu’s soul inside herself, like the Virtues worshipped by the ilykari:

“Don’t look that way,” Yawa said, “you asked. To us a soul is not a great ineffable mystery. People are, after all, not very mysterious. A soul is simply the text of a person’s inner law, and a mind is the act of reading that law into the world. Through study and meditation you can read another soul’s law and copy it into yourself until it comes alive, so that you now have two books of law, two selves, two souls. Himu, Devena, and Wydd all studied and practiced their virtues so completely that they became those virtues. That’s why we emulate them.”

“But I haven’t studied the ykari. I haven’t meditated on a virtue … I just swear by them, very often, I take their names in vain.…”

“No, child. Your obsession was with a woman. Through study and obsession you have built inside yourself the soul of Tain Hu.”

Upon learning this, Baru realises that the second character of her name is the same as that of Tain Hu’s surname (at least in the Alphalone syllabary), and from then on, the narration calls her Barhu.

It’s easy to see (and, probably somewhere explicitly pointed out) parallels between what Barhu’s got going on, and the Cancrioth’s own belief in the transmissibility of souls.

Barhu’s near-lobotomy experience does not link the two halves of her brain and give her integration. But it is enough to do two things: to give her reason to start trusting herself again, rather than seeing Farrier behind every action she might take; and to win Xate Yawa around, as Yawa recognises her at last as someone pursuing the same cause by similarly awful means.

This is one of the first true friendships Baru has had since the death of Tain Hu—one where she is no longer keeping secret her fundamental goal.

What is there to say about this, if this is truly to be a commentary, and not a plot summary? Of course, this is a necessary step: if Barhu is ever to achieve something resembling recovery, she has to reconcile herself to tulpa!Tain Hu. This was well set up by the previous book—Yawa’s explanation is really nothing new—but it is a relief to see Baru finally reach the bottom of her downwards spiral, and understand herself a little better.

I mean, she also gets meningitis from it, but in terms of character arc, she’s past the worst, and on to the long hard project of building meaningful relationships not built on trauma, lies, and blackmail. Which is, overall, the theme of this book: Barhu slowly builds up genuine personal connections with the people she’s wronged, and starts thinking of a way to ‘butcher’ Falcrest that is not apocalyptic.

And as for the nature of the ‘tulpa’ itself? Yawa describes Tain Hu as a ‘law’—a person, here, is described by a way of thinking and behaving. This will align with the book’s notion of culture, which we’ll come to in a little while.

What is a wound?

This takes us up to chapter 9. Having broken the back of Farrier’s despair-conditioning, having at last adopted a little of Tau-Indi’s philosophy and put the immediate good of those around her over her long-term schemes, Barhu still has to figure out what she and her comrades are going to do about Falcrest. But first, she has a few atrocities to witness. She needs to understand the nature of genocide, and such-like things. We will consider Barhu’s plan, and whether it really represents a positive future, shortly. But in terms of Barhu’s personal development, what is now at stake?

To Tau-Indi Bosoka, Baru was a ‘wound in trim’, the network of personal connections that unites the Mbo and everyone else in humanity. To a ‘fundamentalist’ like Tau, who believes in the Mbo’s stories about how they absorbed their would-be conquerers and drew them into mutually supportive relationships, the answer to Baru’s trauma and the harm she’s doing is a kind of restorative justice: they must connect her to others in a genuine way. Tau’s own strength, they believe, comes from the network of personal connections they have as a Prince of the Mbo. And when the Cancrioth declare them severed from trim, making them a wound just as much as Baru, they fall into despair. Later, they start to recover from it, deciding that, even severed as they are, they can still act ethically.

About halfway through the book, Tau, on hearing about Baru attempt to sacrifice herself to save Ulyu Xe, comes up with a theory:

An awful brittleness in Tau’s voice: like ice on the verge of melting, warming but losing strength. “I think it is possible that the Womb’s spell of excision had, ah”—their voice cracked—“had effects she could never anticipate. Baru Cormorant was a wound in trim, an upwelling of grief, a hole. All those who knew her would find only abandonment and regret.

“But when one bond is cut, Iraji, the loose thread may fasten on another. I was cut loose. There were many, many threads seeking a place to fasten.…”

We probably don’t accept Tau’s interpretation, but Baru is increasingly internalising Tau’s philosophy: after she survives Yawa’s lobotomy table, she starts referring to trim to guide her actions, only devising after-the-fact justifications in terms of concrete gain. She tries to go ashore in Kyprananoke, before a certain event renders that futile, and help negotiate for release of water and advise people on containing the Kettling. She reconciles herself with the Tain Hu in her head when circumstances and drugs let her reconnect.

So this book is Baru stitching herself back into trim—in the metaphor she devises to Tau, like a spider reeling itself back into the social web. She is at last reunited with Aminata, and tells her some of the truth, though Aminata has her own arc of disillusionment with Falcrest to follow before she can come over to Baru’s little faction. She gets to know Iscend Comprine, even almost has sex with her at some point, though she’s still unable to believe the Clarified can defy their conditioning to act for Falcrest, still convinced that Iscend’s gradual process of escape is just a fantasy she’s playing out for Baru. She reconciles with Tau, in part on the basis of the above theory, and finally meets Abdumasi Abd, and treats him as a person, and in so doing manages to form a crucial alliance for her new grand plot. Even Tain Shir takes a different view of her.

And she finally meets her parents again—but we’ll get to that later!

A ‘wound’ in trim is thus the behaviour of someone who cannot be vulnerable, someone who can’t exist in a dynamic, stable relation to other people, and interacts through treating people instrumentally, through acting out trauma. To close the ‘wound’ is to create relationships with someone who does not have any, which give them space to find a new way of existing. I think there is something powerful in this, something reflected in the philosophies of restorative and transformative justice—but this is not enough in itself.

The danger is already apparent in the book: trim can declare exceptions, render certain people enenen, non-persons who are not subject to trim. In the Story of Ash chapters, a group of grieving Oriati people attempt to make such a declaration of Farrier and Torrinde, calling for their death; Tau and Kindalana (who I’m getting to!) intervene ritualistically, dressing up in the regalia of Oriati Princes and reminding the crowd of their philosophical/religious commitments—to hospitality, and to deescalation. But the Cancrioth remain enenen.

In a more simple case, a rich person can have deep, fulfilling relationships with other rich people, and still treat a homeless person, or the server at a restaurant, like dirt. Personal connections as celebrated in trim are necessary, but not sufficient. I don’t think the book fails to realise this at all—this is just what I am thinking, considering the proposed philosophy of trim.

Genocide

The Tyrant Baru Cormorant does not use the word ‘genocide’ directly, but it discusses it at several points.

The Kettling plague on Kyprananoke has broken quarantine and spread out of control. Due to its long incubation period, ships could carry it to other ports before realising they are infected—Kyprananoke has become a plague bomb, threatening the rest of the world. Baru notes with disgust that the brain must have chosen Kyprananoke precisely because there’s a chance the plague may be contained.

The plague has also opened the door to a complete collapse of the social order, and factional violence between the Kyprists (former Falcrest puppets) and various groups of Canaats. Certain factions of Canaat are, with weapons such as machetes, attempting to purge anyone with signs of surgery or any other evidence of allegiance to the prior regime. To a Falcresti observer like Juris Ormsment, there is little question that the new regime will be as bad as the old, because of the necessities of holding power:

She turned her spyglass on the kypra islands. The first thing she saw was a raft of corpses swarming with crabs. Most of the capital islet Loveport had gone up in fire overnight, torched by Canaat rebels. Now that the initial rush was over, both sides were busy consolidating their territory and purging their ranks. Anyone with insufficient commitment would be killed as a collaborator; anyone who refused to denounce and punish collaborators would be killed as an enemy of the revolution (or of the state). It would go this way because that was how it had happened in Falcrest, after Lapetiare’s revolution. In a few weeks the Canaat leaders would turn on each other, and the winners would build a new government as cruel and selfish as Kyprism, because if they were not cruel and selfish they would be torn down by those who were. And the cycle would begin again.

Baru, meanwhile, resolves to go ashore anyway in her newfound deontological idealism, to help negotiate a truce for water, and manage plague. She owes, she says, these people her solidarity: after destroying one revolution on Falcrest’s behalf, she wants to do the right thing this time.

Falcrest, however, has an eventuality in place: it has created an ‘apocalypse fuse’, charges designed to explosively collapse one wall of the caldera near the island, so that the displacement wave will be concentrated by the remaining walls. This will create a ‘megatsunami’ that will rapidly wash over the entire island, killing everyone in one stroke. This somewhat complicated plan is inspired by real events: in 1958, an earthquake near Lituya Bay, Alaska caused a similar concentrated wave which completely scoured the trees up to 524 metres from the normal sea level. In 1963, a landslide into the filling Vajont dam reservoir created a wave over the top of the dam, which wiped out several downstream Italian towns.

Naturally, this Chekhov’s superweapon is fired—fired by Iscend Comprine, acting without orders, after none of the cryptarchs are prepared to pull the trigger. (In fact, Tain Shir is even asked to disable the weapon, but arrives too late.)

Even in the throes of meningitis, Baru is unequivocal on one point: the horrors of the Kyprananoki ‘democlysm’ are ultimately of Falcrest’s making. She expresses this point repeatedly throughout the book…

many quotes

To Svir:

“The rebels will be blamed,” she gasped. “Because all their evils are done in the open. The Kyprists are worse—they just make their crimes into laws—you must be sure it’s remembered! There was a tree where Canaat dashed children to death. But the Kyprists had jails, jails where they did as much and more.…”

On the island, after she witnesses a Canaat warband carrying out horrific massacres and training themselves to commit further violence through corpse-mutilation and deliberate disregard for Falcresti sanitation:

They were insane. They were insane and it made perfect sense to Barhu because this madness was, like her, made by Falcrest: a pattern of authority by bodily violence which remained, like a scar, after Falcrest departed.

This terror was ultimately created by the Kyprists, by their ruthless barbers and their use of mass thirst as a weapon. Kyprism was in turn an artifice created by Falcrest’s decapitation of all Kyprananoke’s traditions and the installation of a biddable new ruling class. No matter how vivid and imminent the horrors here, Falcrest was in a distant but powerful way responsible.

But Barhu could not bring herself to forgive the Pranist and his warband.

No matter the cause, these were people doing evil. To absolve them of guilt would be to deny their humanity, to deny that they had some intrinsic dignity and moral independence which only they could choose to surrender. To say that these people were doing monstrous things entirely of their own monstrous nature was to deny Falcrest’s immense historical crimes. But to say that these people were doing monstrous things solely because Falcrest had made them into monsters was to grant Falcrest the power to destroy the soul: to permanently remove the capacity for choice.

In a dream with Tain Hu:

She had learned how people could disembowel themselves. She had learned about the grove of smashed children, the sinkhole full of corpses, the terrible crimes committed in the name of revolution.

But the savagery and the barbarism were ultimately Falcrest’s. Falcrest had destroyed Kyprananoke’s old laws and agriculture. Falcrest had put merchants and barbers in charge, ordered them to stamp out disease, to maximize profit. Falcrest had erased Kyprananoke’s history and replaced it with a sketch of cleanliness and exploitation.

Later, Baru tries to explain what she saw to a group of Taranoki people in effective exile:

“You don’t understand!” But how could they? How could anyone who hadn’t seen it? “Listen,” Barhu begged them. “Kyprananoke was Falcrest’s holding before we were. When they were done with Kyprananoke they left. But it didn’t stop. The people they’d set in power held their posts. The wounds they’d cut kept bleeding. All the old ways of agriculture were gone. All the old ways of justice were disposed of. All the water was in the hands of tyrants. Things got worse and worse. There was resistance, and revolution, but it was as hard and cruel as the regime it fought. And when the situation became so terrible that it endangered Falcrest, they reached out and wiped Kyprananoke off the map. Everyone there is dead. They tried to get free of the chains Falcrest left behind, and Falcrest killed them all for it.

What took place on Kyprananoke, and what is in the process of happening on Taranoke, Baru considers far worse than one would conclude a direct reckoning of number of deaths. Baru’s world does not have a notion of genocide, which in our world was only recognised as a specific crime and entered international law in the years after the second world war (in part thanks to the writing of Raphael Lemkin linking the Holocaust to prior genocides, like the Armenian one).

But even without the word, when she speaks of destroying a culture in this way, genocide is what she has in mind. To Baru, a culture is defined by a particular way of living in the world—a set of practices that are adapted to a specific location, in ways that may not be obvious to Falcrest’s notion of scientific superiority. This comes out in a later conversation with Ulyu Xe:

“When Falcresti sailors arrived they thought the nardoo seeds would be good provisions for long voyages. But the crushing, the washing, and the cooking are all time-consuming and dull. So the sailors skipped the simple women’s work, milled the seeds into flour, and used the flour for bread. And they ate the bread, and shat their bodies out, and starved. They had all the best of Incrastic science and they couldn’t figure out what the Devi-naga all knew.

“It’s as if…” She groped for a way to say it. “It’s as if all the people who live anywhere in the world, no matter how primitive or savage Falcrest says they are, are accumulating interest. Learning things which can only be learned by being who they are, for as long as they have been. Oh, damn it, am I just calling them stupid? Am I just finding roundabout ways to say that these people are too backward to do science?”

“That’s a Falcrest conceit,” Xe countered. “We’re saying they’re clever in a way that’s not valued by Incrasticism.”

“How? How is it clever to do whatever your ancestors teach you?”

“Because your ancestors are smarter than you. Not any one of them, but all together. All those different ways of seal-hunting and flour-making combining and leaping down from generation to generation, sieved out by centuries of practice until only the best forms remain.”

Falcrest’s genocide of Taranoke is not just the extermination of a quarter of the population, but the disruption and attempted annihilation of the patterns that the Taranoki people were living out prior to their arrival.

Of course, ‘genocide: bad in fact’ would not be a particularly novel thing to say. What I want to note here is how this fits into the broader themes of the book: the ecological angle it takes on life. In this view, cultural evolution is like speciation and radiation; genocide is extinction. A culture is a pattern of behaviour, perhaps—but what is an organism but a pattern of behaviour of atoms and molecules and so forth, one which can reproduce itself through time?

This view of a way of life as ‘possessing’ something, which can be lost, is not so far from the UN’s own definition of genocide, which begins:

Genocide is a denial of the right of existence of entire human groups, as homicide is the denial of the right to live of individual human beings; such denial of the right of existence shocks the conscience of mankind, results in great losses to humanity in the form of cultural and other contributions represented by these human groups,

Baru takes a similar line, thinking of Falcrest’s aspirations to conquer and ‘digest’ the Oriati Mbo:

(…)And there were other good things in all the peoples of the Mbo, things no one could imagine or invent, ideas which could only be produced by being who they were, in the places where they lived, with the history they had.

Oriati Mbo was a book of incredible and unread wisdom. A book made of millions of living souls.

And Falcrest wanted to erase the book. Burn the pages for kindling, the people for labor. No one in Falcrest understood that there was anything written in it at all. They believed that some societies were civilized and some were primitive and that the civilized had nothing to gain from the primitive at all.

This notion has some power—at least in terms of recognising a culture as a living process, one that is evolving, not something static and eternal. But I also think there is a danger in framing genocide all about what a group might contribute (to whom? they already have it), even while recognising that part of the justification process for genocide is to deny the creations and accomplishments of the targeted group. Even were the dynamics of a certain group somehow provably reducible to things which existed elsewhere, even if it was true that the ‘civilised’ had nothing to gain on their terms, genocide would be evil. But that’s kind of obvious, perhaps.

Barhu’s emphasis on gain and loss perhaps comes from her own, personal preoccupation with trade—something which will prove to be at the heart of her plan to destroy Falcrest. And Barhu’s faith in the power of trade comes because she can see, at least in part, the significance of exponential growth.

The number of interest

In taking this ecological reading of culture, I am reminded of something Seth wrote on their Twitter—unfortunately I can’t get the direct quote—about the parallels between cancer and colonialism: a part of an organism or community ceasing to participate in symbiosis, but attempting to gather all resources to itself. (Seth said it better.) Let’s look at the thing that unites all the powers, and evils, explored by Baru Cormorant books…

Here are a few recurring motifs:

- economic growth

- disease epidemics

- cancer

- colonialism

- radioactive materials

What do these have in common? In mathematical terms, there’s one obvious point of unity: exponential growth and decay.

An exponential function is something which appears whenever the rate of growth of something is proportionate to how much is already there.

That may sound a bit confusing, so let’s consider an example. Imagine a population of elephants, with plenty to eat. The more elephants there are fucking and making baby elephants, the more elephants will be born each generation. When you only have two elephants, the population grows very slowly… but as the herd gets bigger, the elephants appear faster and faster. Over a great many generations, it produces a curve a bit like this: