originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/113395...

lesbianmooncolony asked:

assuming a starship never has to travel through an atmosphere, and never has to worry about collisions with eg. asteroids or attackers' weapons (maybe some sort of forcefield, or a perfect interceptor weapon system), are there any compelling reasons for starships to be any particular shape? (let's also assume the starship can travel at relativistic speeds)

Aha! Excellent question! I love talking about spaceships.

So most of what I know comes off Atomic Rockets, which has far too much love of old whitedude science fiction novels, but also a lot of useful information, and more recently, lots of conversations with arborine, who has thought/knows a great deal about space habitats and is generally wonderful.

There are a few design considerations that constrain what shape your spaceship should have…

- it needs to bear the stresses of acceleration without breaking

- it needs to dissipate the heat generated by the crew, onboard machinery and direct sunlight into the highly insulating vacuum of space

- it needs to be able to manouvre correctly and, for example, not start spinning uncontrollably when the engine does a burn

- its rotation needs to be long-term stable in flight

- it needs to be able to withstand impacts with interplanetary/interstellar debris, which although consisting only of rarified gas and small particles, may (depending on the mission) may be approaching at extremely high, even relativistic speeds

- it needs to protect equipment and crew from space radiation (from stars or cosmic rays)

- it needs to protect the crew from any radiation produced by the ship’s engines, or its power source (a big issue if you use something scary like nuclear power or antimatter annihilation!)

- if humans are on board it needs to have pressurised compartments for them to live in, and enough space that they will be comfortable for the duration of the voyage

- it needs to minimise the extent of the damage if something goes wrong, e.g. part of the ship is depressurised

- it needs to survive for the entire length of the voyage, which probably means it needs to be self-sustaining

- it needs to carry enough propellant reaction mass to give it the \(\Delta v\) for whatever it’s out there to do

- it needs to be as light as possible, because every unit of mass of spaceship also adds a lot of units of reaction mass, depending on the mission \(\Delta v\)

- if you want the crew to experience artificial ‘gravity’, it either needs to be capable of accelerating near \(g\) for nearly the entire mission, or have sections of the spaceship capable of rotation to create a centrifugal force near \(g\)

I’m sure there are a lot more of them.

So while there’s no reason for your ship to be streamlined, there are a bunch of constraints!

1. make it strong, and maybe put the engine at the front to save mass

The first one depends a lot on where you position your rockets. Most designs place the propulsion at the back of the ship, pushing the ship forwards.

If you put the propulsion system at the back of the ship, you need your ship to be sturdy against compressive strength, which adds to the mass of the mission - compressive strength usually requires massive beams and so on, and it’s hard to get around that. When you’re accelerating, it will feel as if gravity is pushing down on everything on board towards the back of the ship, and like a building, your ship has to be strong enough to stand up. Otherwise, your engine will punch straight through your ship, or crush it, or tear off, or something similarly bad.

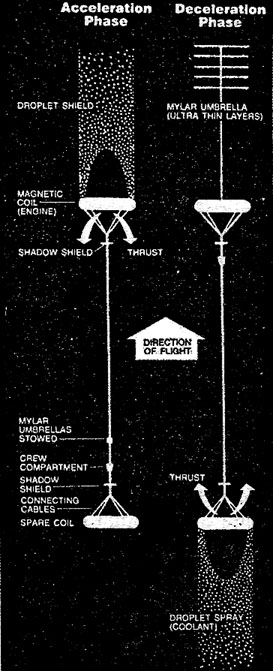

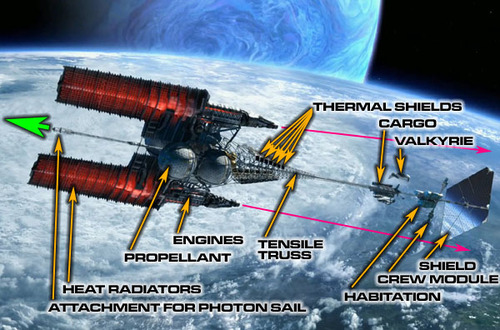

A tiny number of designs, like the Valkyrie, and in fact some of the earliest rockets ever built, have the propulsion at the front of the ship, towing the rest of the ship behind it.

If you do that, your ship needs tensile strength to not snap against the propulsion. You generally don’t need as much mass to have tensile strength as compressive strength - but putting the engine at the front does mean your crew are directly in the path of the engine exhaust! (The radiation problem is a general one for nuclear and antimatter engines, but it’s particularly severe when you’re right in the engine beam…)

The Valkyrie gets around this by having a shadow shield between the engine and the crew compartment, which absorbs radiation from the engine and casts a shadow over the crew compartment.

Another option is to have your engines not point directly backwards, but have two or more engines angled slightly out to the sides in opposite directions - this is apparently what the ship in the film Avatar does (ship’s presumably a still from the film, annotations from Atomic Rockets).

Putting the engines at the front on a flexible tether does make it much harder to change direction, though.

2. make sure it has large flat surfaces, or sprays of recoverable droplets, to act as radiators

Although space is sometimes described as ‘cold’, especially in movies, that’s kind of misleading. Certainly, if not in direct sunlight, something in space without a heat source will eventually cool down until it’s incredibly cold… but for the same reason that we use vacuum flasks to keep tea or whatever warm, it takes a very long time.

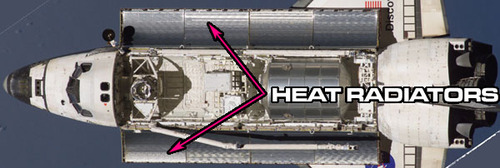

If you’ve got something like a spaceship, which is generating a lot of heat, you need to do something to dissipate that heat. The only mechanism that heat can be lost in space, with no atmosphere to carry it away, is electromagnetic radiation. To lose heat through radiation, you need a large surface area (i.e. big flat surfaces called ‘radiators’), and to carry the heat from the rest of your ship to the radiators. You heat up the radiators and they radiate away your heat into the vacuum.

The Space Shuttle would apparently open its cargo bay doors in space to help it radiate away heat (labels once again from Atomic Rockets).

Your radiators should not have their surfaces facing each other, or else they will heat each other up, and won’t radiate heat as effectively.

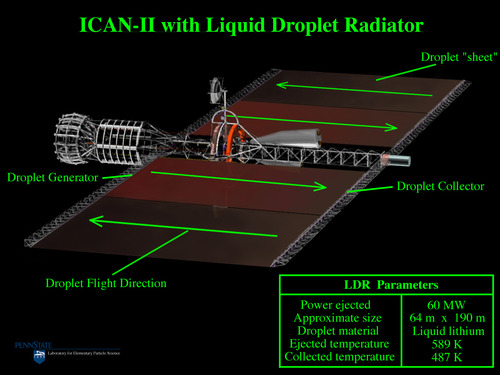

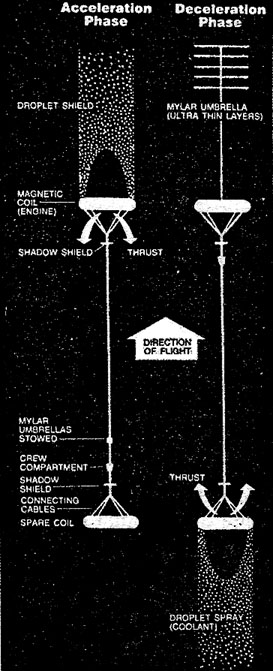

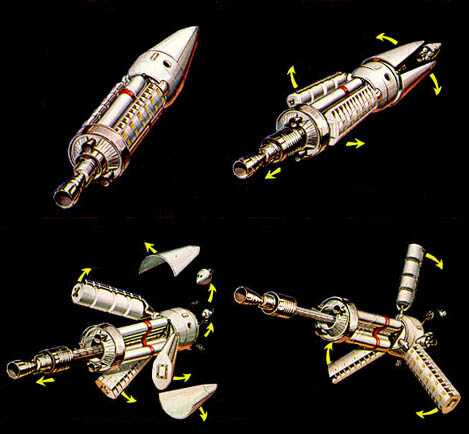

Another trick to cool your ship down is to use a ‘Liquid Droplet Radiator’ (picture source - apparently the ‘ICAN-II’ design from Penn State University, no idea what that stands for). This involves using your waste heat to heat up a spray of hot liquid droplets, which travel through space, steadily cooling down. As your ship is accelerating, the droplets ‘fall’ towards the back/front of the ship (depending which way you go), and can be collected, heated up and sprayed back in the opposite direction, maintaining continuous circulation.

Atomic Rockets has some really weird-looking designs, including discs, triangles, and even one that looks like a spiral (using magnetic fields).

Have a look at Atomic Rockets - there are lots of radiator designs I haven’t covered, involving bubbles, nanotube filaments, all sorts of stuff.

3. make sure the thrust vector goes through the centre of mass

If it doesn’t - if your engine is off-centre - when you do an engine burn, it will also have a nonzero moment (torque). This means your ship will start to rotate around its centre of mass when you do an engine burn. Sometimes, this is what you want, but usually only by a small amount! And typically a large engine burn would set you spinning wildly. So you will probably have separate small thrusters for turning.

(This gets even more complicated if your ship has flexible elements!)

4. make sure that, if your ship is spinning, it is spinning around its major principal axis

Every rigid body has a thing called its moment of inertia tensor that can be calculated from its mass distribution. Its eigenvalues are called the principal moments of inertia, and its eigenvectors are called the principal axes of the body. When the engine is not burning, the ship is undergoing free precession.

I remember a series of arguments about free precession in our classical mechanics lectures that say, since a not-quite-rigid body slowly loses energy to internal stresses but the angular momentum is conserved, it precesses (the angular velocity vector moves with respect to the body coordinates, if that means anything to you) so as to end up spinning around the principal axis with the largest moment of inertia.

If your plan is that your spaceship should spin around a different axis, you should be worried, because it will slowly precess to spin around the major axis.

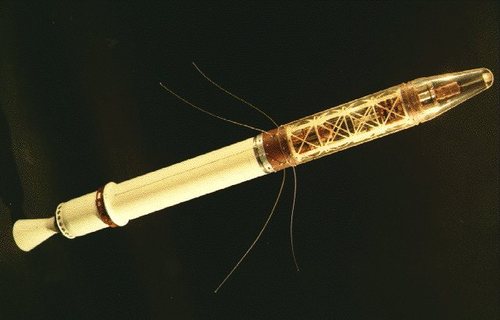

At the time the USA launched their first ever satelite, Explorer 1, in 1958, this was not known. The pen-shaped (shh) satellite was set spinning around its minor axis, the long axis through the middle of the spaceship. To the scientists’ surprise, the axis of rotation changed in flight, until the satellite was flipping end over end. This led to the first development of Euler rotation (the kind of thing we’re talking about) in over 200 years. But we’ve done that now, so, make sure your spaceship is spinning around its major axis if it spins!

5. if you’re going too fast, the ship needs to be safe from relativistic dust

A tiny grain of dust, when raised to relativistic speeds, can have the kinetic energy of a bullet or bomb. And, if your ship is travelling through space at relativistic speeds, every grain of dust in space will be approaching your ship at those speeds! This is bad.

One solution is to put a shield at the front of your spaceship, which will be punched up by relativistic dust, but will disperse most of its energy before it smashes anything important.

I’m going to talk about the Valkyrie again. I am maybe a bit too into this design, but their solution is really cool.

The Valkyrie sprays fluid droplets ahead of the ship. Any incoming particles can detonate harmlessly among the droplets, without touching the engine. Because the ship is constantly accelerating, the fluid droplets will ‘fall’ back down and land relatively slowly on the front of the ship, where they can be recycled. This is also used for cooling - another ‘liquid drop radiator’.

During the deceleration phase of the mission, this doesn’t work - the droplets fly off ahead of the ship instead of being recaptured. The Valkyrie’s solution is to grind its spent fuel tanks into fine dust and release them ahead of the ship as it decelerates. Travelling at a constant relativistic speed, the ground up fuel tanks will punch their way through any interstellar dust particles ahead of the ship, clearing a path.

Some dust will still enter the path ahead of the ship, so in addition to that trick, the Valkyrie extends many layers of ‘blankets’ of extremely thin material (’similar to Mylar’) ahead of the ship. Because the ship is accelerating in the opposite direction, the blankets are stretched out in front of the ship.

Obviously, nothing remotely close to this has ever been tried! So who knows if it would actually work. I haven’t seen discussion of relativistic dust in other designs on Atomic Rockets, though.

6. you also need to be safe from the ordinary kind of space radiation

Even if you’re not travelling at relativistic speeds, you will (without the protection of an atmosphere) constantly be irradiated by cosmic rays and other ionising radiation from any nearby star. This is a problem even for current astronauts, who apparently hide behind water tanks during periods particularly intense radiation. And it’s often discussed as a major danger of a voyage to Mars.

To an extent, you are protected from this by the hull of your spaceship, which absorbs most kinds of radiation even if it’s quite thin. You apparently need two layers to deal with different kinds of radiation, since charged particles entering the e.g. lead you would use for gamma ray shields can create deadly X-rays. Everywhere where people will be living, long-term, needs to be protected this way.

During periods of major radiation, such as solar flares, this may not be enough. You need a particularly well-shielded part of your spaceship to hide in at these times. One method is to use the water (that you’re carrying anyway, for the crew to drink) to protect the crew at these times. You need a way for the crew to access this area, and take anything particularly vulnerable to radiation - such as food - in there with them.

Apparently people are also considering other methods, involving things like powerful electric or magnetic fields, or bubbles of plasma. I don’t know a lot about this.

7. you also need to be safe from the radiation from your ship’s propulsion and power plant

To travel long distances in space, chemical rockets tend not really to be enough - you need something with a very high \(\Delta v\). Many such propulsion systems have been designed, but they tend to have the side effect of producing lots of ionising radiation.

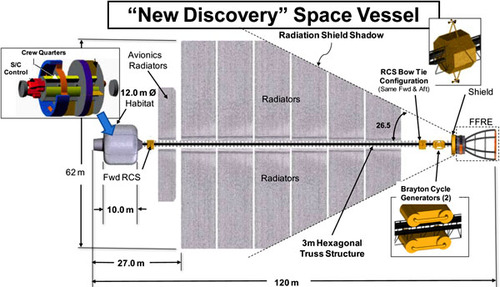

This isn’t necessarily a huge problem. You don’t necessarily need to shield your entire reactor (which would be very heavy), but can instead use a shadow shield, like we discussed on the Valkyrie, to keep just your ship safe from the radiation, and let the rest of the radiation radiate away into space. But it does imply that the rest of the ship, including your thermal radiators, needs to keep itself inside the cone of safety created your shadow shield. And your shadow shield is usually still quite massive, because the main way we attenuate radiation is to make a lump of very dense materials.

Here’s an example of a NASA design which uses a shadow shield, and has to keep its radiatiors inside the shadow:

8. it needs to have pressurised areas for humans to breathe in

The pressure outside the spaceship is nothing. The pressure inside the spaceship is probably about 1 atmosphere. Your ship needs to be strong enough to contain that.

You definitely don’t want to have too many parts of your ship that would be particularly vulnerable to rupturing, so the walls of your pressurised areas are probably going to be nice and curved with minimal sharp corners.

One way to build a pressure vessel, the way we currently do, is to use lots of strong metal. But that adds a lot to your payload mass. So another possibility is to have an inflatable spaceship.

NASA has one such design called the TransHab. Which I assume means it can’t be boarded by cis people. It looks like this (source)…

(all of those weird CGI people are trans. no arguing)

arborine has generally talked about much larger, long-term designs: a big sphere or torus, containing a much more comfortable landscape built for many people (I will have to ask her to help me recreate the details though!). Spheres and toruses are good for inflatable shapes, because the tension is nice and even across the surface (well, this is complicated by rotation, but basically).

The need to have a pressurised hull and radiation shielding does introduce some limitations. Windows in a pressurised compartment generally need to be quite small and rounded, like aeroplane cabin windows, but when you’re far from a planet, there’s not really anything to see anyway. (It seems that, with sufficient engineering, you can make bigger windows, such as in the ISS’s observation bubble thingy. Even then, the bubble’s pretty small, and there’s plenty of structural stuff keeping that together.)

9. you need to be able to deal with problems with mimimal damage

Despite all your best efforts, it seems inevitable that a pressurised compartment travelling through the vacuum of space might have something go terribly wrong. For example, something punches a hole in the hull. You need to have that not end the mission, and cause as little harm to the crew as possible.

This probably means, internally, that your ship needs to be divided into separate compartments, so that if one gets depressurised, the rest of the ship is still safe. If the walls of your ship can somehow be self-sealing, even better.

10. you need self-repair and a self-renewing ecosystem for a long voyage

If you’re travelling on a very long voyage, carrying supplies for the entire journey just takes too much mass. You need to carry with you a functional, lasting ecosystem of plants etc. that won’t die off during the voyage.

Making a closed ecosystem is very hard - as far as I know, we haven’t succeeded yet. I will defer to arborine on the details of one, as I can’t remember what she said or what was in her extremely practical space habitats book off the top of my head.

In addition, parts of your ship will slowly fail and go wrong. Atomic Rockets claims the best NASA probes can last 40 years in space, and that may well not be enough for your purposes (even taking as much advantage as possible of relativistic time dilation). For a very long voyage like a generation ship or something, everything can probably be assumed to go wrong your spaceship to an extent needs to have the capabilities on board to build itself, and apply its repairs outside the safety of crew compartments.

Needing to recreate them en route might constrain the materials you can use, and hence the shapes you can make.

( breathofzephyr made an interesting point that the total computing power, data storage etc. available to the crew of a generation ship will, unless they can build more computers, go down over the course of the mission. which could have interesting social effects…)

11. you will probably need to dedicate a lot of your spaceship to storing reaction mass in suitable containers

A consequence of the rocket equation is that, for every gram (or whatever mass unit) of payload - structural elements, people, food, computers, robots, whatever - you have, you will need a certain number of grams of reaction mass to throw out the back of your rocket.

(The exception is if you are using a propulsion system such as a solar sail or a laser sail where you are propelled by collisions with material that you’re not carrying with you. Or if you’ve figured out a way to get the Bussard Ramjet, or its variants, to be practical!)

The shape of your propellant tanks depends a great deal on what kind of engine you’d use, but basically, you need a lot of pressure vessels somewhere on your ship, likely held separate from the crew modules.

12. it needs to be really really light, as far as possible

The rocket equation is a very demanding thing, and unless you somehow have vast amounts of leftover \(\Delta v\), you want to take every possible opportunity to save on mass. (’loads of leftover \(\Delta v\) is like, you’re using Project Orion to travel through the solar system or something.)

This is why lots of spaceship designs are modules held together by a lightweight framework - you want to minimise heavy structural elements as much as possible.

We’ve talked quite a bit about this already, though!

13. if you provide gravity, you either need a lot of \(\Delta v\) or something has to spin

For a long voyage, your crew’s bones and muscle will atrophy unless they’re given an environment with a source of ‘gravity’ similar to Earth’s.

There are two ways you can do this, which amount to accelerating some or all of your spaceship. One way is to have your engine burning so as to provide \(1 g\) acceleration throughout your voyage. By contrast, current space missions usually involve very short rocket burns, with the spaceship flying freely for most of its mission. To burn throughout the mission, your ship will need vastly more \(\Delta v\), and hence vastly more propellant mass per unit payload mass.

Since that’s pretty demanding, the other option is to have part of your spaceship spinning. This could be for example a toroidal ring, or a cylinder, or a sphere, or a couple of rooms on the end of long arms.

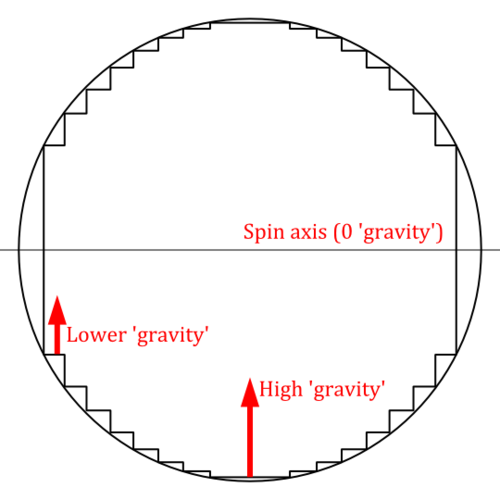

Depending on how large your rotating section is, it will have to spin more or less fast in order to maintain the amount of gravity you need. The centrifugal acceleration in a rotating reference frame is given by \(r\omega^2\), where \(r\) is the distance from the centre, and \(\omega\) is the angular speed.

Note this means the artificial ‘gravity’ in a rotating section with multiple floors, or in a spherical habitat, will vary as you get closer or further away from the centre! The further out you are, the stronger gravity will be.

A rotating habitat section has some implications about the design of the inside. ‘Level’ surfaces will be curved instead of flat, and the Coriolis effect will apply to deflect trajectories from a straight line - particularly strongly in a small, fast-spinning section.

There are lots of difficulties to overcome if only part of your spaceship is spinning. A major one is the problem of the bearing between the rotating section and the rest of the ship - it needs to be near frictionless, or your spin section will slowly spin down (and your ship will slowly spin up.

Another problem comes from spinning up your spin section without setting the rest of your spaceship rotating in the opposite direction (with possible consequences of precession, and the like). One solution is to have a flywheel inside your ship, but this implies a large mass that’s generally useless. Another is to have multiple counter-rotating spin sections, such that the net angular momentum change can be 0 without spinning the entire ship.

Or, you can just let the entire spaceship spin at once, though this makes manouevring the ship somewhat complicated because of the way gyroscopes act (it becomes forced precession, and you need to push at \(90^\circ\) from the way you actually want to turn…)

A further problem comes from the fact that, when your spaceship is accelerating, the direction of ‘down’ will change. This can be accomodated by some very complicated-looking designs involving arms that swing in and out (source), or just ignored because most of the time your ship is not accelerating.

and more stuff, probably

So, yes, there are a lot of physical demands on the shape of a spaceship, even one that never visits an atmosphere!

Building a spaceship is a lot different from building on Earth, and of course nobody actually knows how to build a spaceship for an interstellar voyage. But this is what we think, based on the physical constraints we’ve imagined so far…

Comments