originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/118148...

Considering that the situation is entirely impossible, ‘what would happen if you drilled a tunnel through the Earth and jumped in’ is a surprisingly commonly-set physics problem. Perhaps mainly because of its counter-intuitive result: whichever two points on the surface of the Earth a uniform density sphere your straight frictionless tunnel connects, it takes exactly the same time to fall the length of the tunnel.

How can that be!?

The basic idea is that, although shallow tunnels between nearby points are shorter than deep tunnels between widely separated points, you accelerate much less along the shallow tunnels so it works out the same.

OK, so, lets lay out the problem.

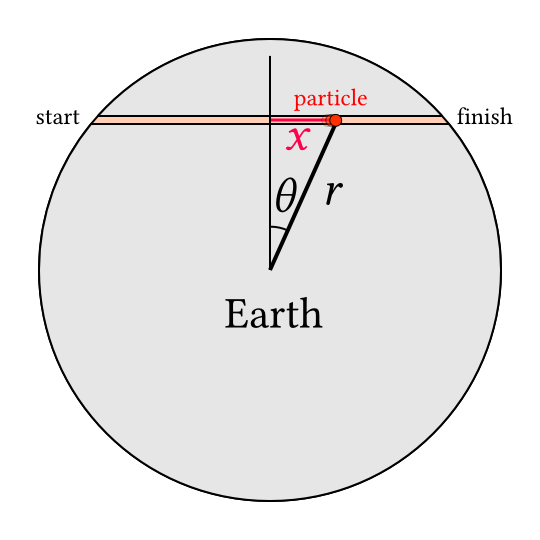

We have a spherically symmetric, nonrotating nonaccelerating ‘Earth’ with a frictionless tunnel through it. An object called the particle can move along the tunnel.

- We’ll call its position in the tunnel \(x\) and the length of the tunnel \(l\)

- The starting point is \(x=-\frac{l}{2}\) and the finishing point is \(x=\frac{l}{2}\)

- Its distance from the centre of the Earth is \(r\)

- There is an angular coordinate, \(\theta\), and we have \(x=r \sin\theta\)

- the tunnel passes within a distance \(y\) of the centre of the Earth, so \(r^2=x^2+y^2\).

The Earth is course not actually any of those things! It’s an oblate spheroid rather than a sphere, it’s rotating, and it’s constantly being accelerated by the sun. And a frictionless tunnel is likewise impossible.

We will say the Earth has a varying density called \(\rho (r )\).

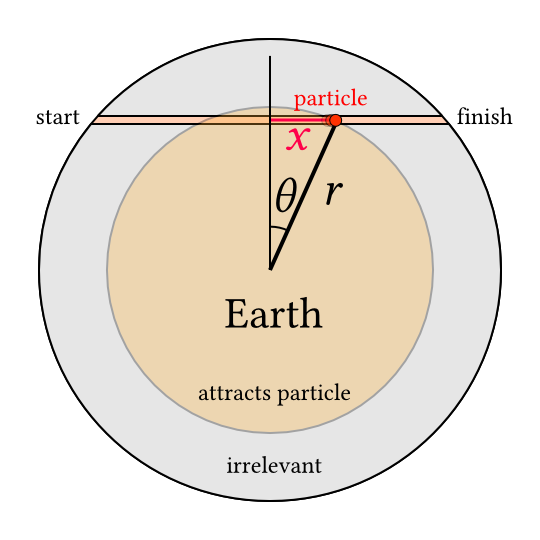

To find the motion we take advantage of something called the shell theorem.

The shell theorem says

- the gravitational acceleration of a particle inside a spherically symmetric shell of matter is 0, regardless of where the particle is in the shell.

- the gravitational acceleration of a particle outside a spherically symmetric mass distribution is exactly the same as if the entire volume was a point mass at the centre of the shell.

So the particle’s acceleration is created by only the amount of matter closer to the centre of the Earth than the particle.

That amount of mass is given by $$\int_0^r 4 \pi R^2 \rho( R) \dif R$$

In free space, the particle would accelerate to the centre of the Earth at acceleration $$a=\frac{G}{r^2}\int_0^r 4 \pi R^2 \rho( R) \dif R$$If we resolve this in the direction of the tunnel, the acceleration along the tunnel is \begin{align}\ddot{x}&=-a(r )\sin\theta=-a( r)\frac{x}{r}\\&=-\frac{Gx}{r^3}\int_0^r 4 \pi R^2 \rho( R ) \dif R\end{align}

I was rather hoping that I could show the result we’re looking for works for a general density profile, but I guess it doesn’t, so let’s now consider the case of a uniform density ‘Earth’. In this case, the integral evaluates simply as $$\int_0^r 4 \pi R^2 \rho \dif R=\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3 \rho$$so the equation of motion becomes $$\ddot{x}=-\frac{4}{3}\pi G \rho x$$which is just the equation of a simple harmonic oscillator! In other words, the particle’s motion is exactly the same as a ball on a spring, or a pendulum undergoing small oscilations: it’s just sinusoidal motion such as (if the particle starts at rest) \begin{align}x&=-\frac{l}{2} \cos \left(\omega t\right)\\\omega^2&=\frac{4}{3}\pi G \rho\end{align}

The period \(T\) of the oscillation is related to the angular frequency \(\omega\) by \(\omega T = 2\pi\) so $$T=\sqrt{\frac{3\pi}{G\rho}}$$which, if evaluated with the average density of Earth, is 84.3 minutes which means the time to fall from one end of the tunnel to the other is about 42 minutes, regardless of the positions of the ends of the tunnel.

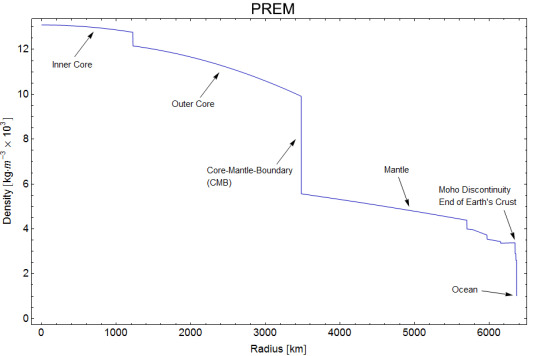

However, this calculation depends on the constant density of the Earth leading to the \(r^3\) term neatly cancelling out. In reality, the Earth has a varying density: the iron core is extremely dense, the mantle much less so.

(graph from Wikimedia Commons, based on the ‘Preliminary Reference Earth Model’)

So, in general, a tunnel through the Earth would not take 42 minutes to reach the other end. (It may be worth revisiting this at some point to try it with some more accurate models…)

Comments